“For every [planet] that we see, we know that there are 10, 100, even 200 others out there in the galaxy that we didn’t see,”

The Milky Way galaxy feels a little more crowded.

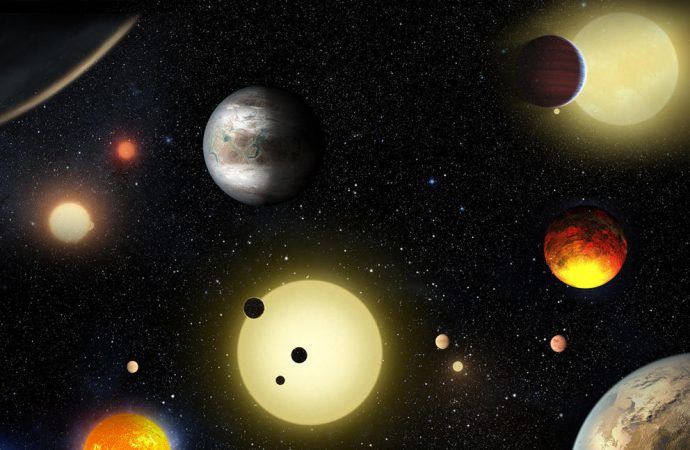

After sifting through data from NASA’s Kepler space telescope, scientists said Tuesday they’ve confirmed the existence of 1,284 planets orbiting other stars in our galaxy.

See the most-read stories in Science this hour >>

The announcement more than doubles the number of validated planets discovered by the veteran planet-hunting spacecraft, bringing the total number to about 2,325.

This bumper crop of new worlds features a host of super-Earths and mini-Neptunes. Perhaps most striking, the new census includes nine worlds that could be rocky and Earth-like, and that orbit their host stars in the so-called habitable zone, where temperatures would allow water to be stable in liquid form.

“We now know that exoplanets are common, that most stars in our galaxy have planetary systems, and that a reasonable fraction of the stars in our galaxy have potentially habitable planets,” said Paul Hertz, director of NASA’s astrophysics division in Washington. “Knowing this is the first step to addressing the question, ‘Are we alone in the universe?’”

The findings, published in the Astrophysical Journal, also present a new technique for validating candidate planets that should vastly speed up the verification process.

During Kepler’s primary mission, the spacecraft stared at a single patch of sky containing roughly 150,000 stars. It looked for the tiny dips in starlight caused by a planet passing in front of its star.

From its launch in 2009 to the crippling of its second of four reaction wheels in 2013, Kepler identified more than 4,500 possible exoplanets of all sizes, from super-Jupiters to Mars-sized worlds.

But many celestial phenomena can mimic a transiting planet. A brown dwarf might pass in front of a larger one. A binary system, in which two stars circle each other, can also fool Kepler’s unblinking eye.

So researchers have gone to great lengths to confirm each candidate exoplanet on a case-by-case basis, following up with observations from telescopes on the ground and using techniques that are tailored for each situation.

“One of the biggest challenges for Kepler is that these follow-up observations that have been traditionally used to verify planets are time- and resource-intensive,” said Timothy Morton, an associate research scholar at Princeton University and lead author of the new scientific report.

So Morton devised an algorithm that uses the power of probability to speed up the process. It combines two pieces of information – how well does the observed signal resemble that of a real planet, and how common are fakes – to conduct a detailed analysis that can confirm planets with roughly 99% reliability.

The scientists also used it to verify 984 exoplanets that had already been confirmed using other techniques.

In its first few months of work in orbit around the sun, Kepler sent back loads of potential planetary finds. But astronomers were deeply cautious, in part because earlier ground-based transiting surveys had such high false-positive rates that they’d end up discarding more than half of their signals, said study coauthor Natalie Batalha, Kepler mission scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center.

“We were prepared to have to throw away 60% to 70% of the candidates,” Batalha said. “Tim was the first person to critically examine that assumption.”

When Morton’s technique was applied to a group of 4,302 candidate planets – 984 of which were already validated – the researchers were able to confirm 1,284 more. Of the remainder, 1,327 were deemed likely planets and the final 707 were classified as likely impostors.

The next task, Batalha said, is to use the population of known planets to determine the far larger number of actual planets. After all, Kepler can only see the planets whose orbits just happen to align with the spacecraft’s line of sight; there could be many more just beyond our field of view.

“For every [planet] that we see, we know that there are 10, 100, even 200 others out there in the galaxy that we didn’t see,” Batalha said. “We are sampling the galaxy to understand how many planets there are, and how far out we have to search in order to find potentially habitable planets like Earth.”

Among the newly confirmed group, close to 550 are no more than twice the size of Earth –small enough that they’re probably rocky bodies like our planet. Nine of these sit in the habitable zone, that ring-shaped region around a star where the temperature is just right for liquid water to remain stable. (In our solar system, that region is roughly bounded by the orbits of Venus and Mars.)

Now the tally of such ideally sized and positioned planets is 21.

“It’s super exciting because it starts to fill in the whole habitable zone,” said astronomer Lisa Kaltenegger, director of Cornell University’s Carl Sagan Institute, who was not involved in the work.

The bulk of the newly confirmed worlds are from categories that have no analogue in our own solar system: super-Earths and mini-Neptunes.

There were relatively fewer Jupiter-sized planets, which were plentiful in the early days of the Kepler mission. In part, that’s because their large size caused dramatic dips in starlight that were easier for the telescope to see. Also, they were often found surprisingly close to their stars, which meant they orbited very quickly and provided more transits for scientists to analyze.

Since gathering all this data, the Kepler spacecraft has moved on from a single patch of sky to gazing at the slice of the galaxy that lies in the ecliptic plane. This mission, known as K2, will end in about a year and a half, a few months before the spacecraft is predicted to run out of fuel, said mission manager Charlie Sobeck.

Scientists are already looking forward to the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS, NASA’s follow-up to Kepler that is set to launch in 2017. TESS will scan not just a single patch or slice of sky, but the entire heavens.

Still, Kepler’s influence will live on, scientists said: The statistical techniques devised by Morton and his colleagues will apply directly to TESS as well as other transit surveys, such as the European Space Agency’s PLATO mission, planned for launch in the 2020s.

Kepler, TESS and PLATO are baby steps in the search for truly Earth-like planets – and perhaps even life, scientists said. But in the meantime, they may fundamentally alter our view of the heavens.

“When you look up in the sky you’re not just going to see pinpoints of light and see them as stars,” Batalha said. “You’re going to see pinpoints of light and see them as planetary systems.”

Source: LA Times

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.