First modern scans of people high on psychedelic drug has given researchers unprecedented insight into neural basis for its effects

The profound impact of LSD on the brain has been laid bare by the first modern scans of people high on the drug.

The images, taken from volunteers who agreed to take a trip in the name of science, have given researchers an unprecedented insight into the neural basis for effects produced by one of the most powerful drugs ever created.

A dose of the psychedelic substance – injected rather than dropped – unleashed a wave of changes that altered activity and connectivity across the brain. This has led scientists to new theories of visual hallucinations and the sense of oneness with the universe some users report.

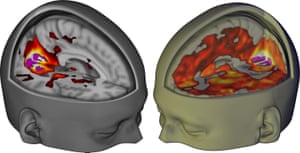

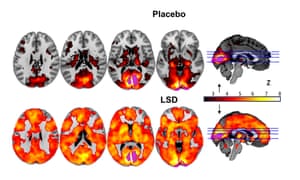

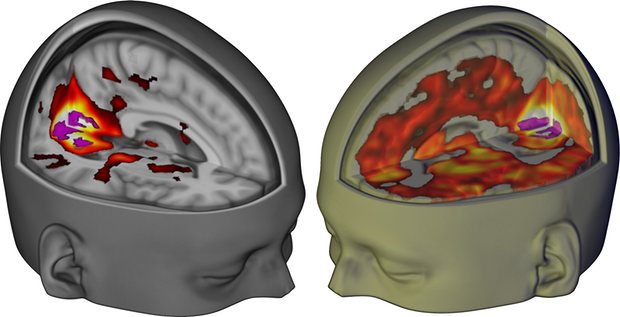

The brain scans revealed that trippers experienced images through information drawn from many parts of their brains, and not just the visual cortex at the back of the head that normally processes visual information. Under the drug, regions once segregated spoke to one another.

Further images showed that other brain regions that usually form a network became more separated in a change that accompanied users’ feelings of oneness with the world, a loss of personal identity called “ego dissolution”.

David Nutt, the government’s former drugs advisor, professor of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London, and senior researcher on the study, said neuroscientists had waited 50 years for this moment. “This is to neuroscience what the Higgs boson was to particle physics,” he said. “We didn’t know how these profound effects were produced. It was too difficult to do. Scientists were either scared or couldn’t be bothered to overcome the enormous hurdles to get this done.”

LSD, or lysergic acid diethylamide, was first synthesised in 1938 but its extraordinary psychological properties did not become clear until 1943. Throughout the 1950s and 60s the drug had a major impact on psychology and psychiatric research, but its adoption as a recreational drug and its influence on youth culture led to it being banned in the 1960s.

The outlawing of LSD had an immediate effect on scientific research and studies into its effects on the brain and its potential therapeutic uses have been hampered ever since. The latest study was made possible through a crowdfunding campaign and The Beckley Foundation, which researches psychoactive substances.

With his colleague Robin Carhart-Harris, Nutt invited 20 physically and mentally healthy volunteers to attend a clinic on two separate days. One day they received an injection of 75mcg of LSD and on the other they received a placebo instead.

Using three different brain imaging techniques, named arterial spin labelling, resting state MRI and magnetoencephalography, the scientists measured blood flow, functional connections within and between brain networks, and brainwaves in the volunteers on and off the drug.

Carhart-Harris said that on LSD, scans suggested volunteers were “seeing with their eyes shut”, though the images they reported were from their imaginations rather than the world outside. “We saw many more areas of the brain than normal were contributing to visual processing under LSD, even though volunteers’ eyes were closed,” he said. The more prominent the effect, the more intense people rated their dreamlike visions.

Under the influence, brain networks that deal with vision, attention, movement and hearing became far more connected, leading to what looked like a “more unified brain”, he said. But at the same time, other networks broke down. Scans revealed a loss of connections between part of the brain called the parahippocampus and another region known as the retrosplenial cortex.

The effect could underpin the altered state of consciousness long linked to LSD, and the sense of the self-disintegrating and being replaced with a sense of oneness with others and nature. “This experience is sometimes framed in a religious or spiritual way, and seems to be associated with improvements in wellbeing after the drug’s effects have subsided,” Carhart-Harris said.

The drug can be seen as reversing the more restricted thinking we develop from infancy to adulthood, said Nutt, whose study appears in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The study could pave the way for LSD or related chemicals to be used to treat psychiatric disorders. Nutt said the drug could pull the brain out of thought patterns seen in depression and addiction through its effects on brain networks.

Amanda Feilding, director of the Beckley Foundation, said: “We are finally unveiling the brain mechanisms underlying the potential of LSD, not only to heal, but also to deepen our understanding of consciousness itself.”

- This article was amended on 11 April 2016 to give the correct amount (75mcg) of LSD administered to each volunteer.

Source: (The Guardian)

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.