Some women are born with hyper-sensitive eyes that can see the world in ways most of us cannot even imagine. What’s it like to live with this gift?

A few years ago, the artist Concetta Antico discovered that she was carrying a genetic mutation that gave her astonishingly sensitive perception of colour – seeing a spectrum of distinct shades where we only see one.

As she told BBC Future in 2014, even the dullest pebble on the road shimmered like a kaleidoscope.

“The little stones jump out at me with oranges, yellows, greens, blues and pinks,” she says. “I’m kind of shocked when I realise what other people aren’t seeing.”

Most of us cannot attempt to contemplate the rainbow she is describing

A seemingly plain green leaf may burst with vivid red shades, while a punnet of tomatoes is a multi-coloured palette of tones – Antico claims she can pick out the ripest fruit at a glance, thanks to subtle differences in its shade that would be invisible to most of us. “The intense colours are speaking to me all the time,” she says today.

In the same way that a colour blind person cannot imagine the variety of reds and greens that most people can see, most of us may not be able to picture the rainbow she is describing.

Back in 2014, the scientific research into Antico’s abilities had only just commenced, but today the investigations are in full swing – with a brand new paper providing some striking insights into her world.

The detailed colour in Concetta Antico’s artwork may help us to imagine what she sees (Credit: Concetta Antico)

It had long been known that people with extraordinary vision like Antico should in theory exist, thanks to an unusual difference in the way their eye is constructed.

Imagine the retina as a kind of mosaic, composed of different kinds of light-sensitive cells known as cones. Most of us have three kinds of cones tuned to different sets of light wavelengths (making us “trichromat”). The light from each part of a scene will activate these cells to different degrees, with the exact combination of signals determining the colour we perceive.

Some women, however, are “tetrachromat”. Thanks to two different mutations on each of the X chromosomes, they have four cones – increasing the combination of colours they should be able to see. The mutation isn’t very rare (estimates of the prevalence vary and depend on your heritage, but it could be as high as 47% among women of European descent), but scientists struggled to find someone who reliably demonstrated enhanced perception.

Then Antico came along, passing a string of tests that showed her vision was different. Studies proved that her tetrachromacy gave her enhanced vision in low lighting – allowing her to see astonishingly vivid scenes at dusk, for instance. After BBC Future broke the story, she soon became famous as the “woman with rainbow vision”.

Even if you carry the right versions of the genes involved in colour perception, training may be crucial to cash in on your genetic potential (Credit: Getty Images)

Even so, many questions remained. Given that many women may be carrying the mutation, why do so few people prove to have such astonishing vision, for instance? “One possibility is that you need early training to capitalise on the signal,” says Kimberly Jameson at the University of California, Irvine, who has tested Antico extensively. Antico is an artist, who has paid close attention to subtle variations in colour for almost all of her life. “I was fairly manic,” Antico says today. “I always wanted to represent everything I could see.” Perhaps this kind of intense experience was crucial to rewire the brain so it could cash in the extra signals her eyes were receiving.

To find out, Jameson teamed up with Alissa Winkler at the University of Nevada, Reno, to compare Antico’s vision to a range of other participants, including another tetrachromat who was not an artist, and also an artist who had regular vision.

Even when I found out I had tetrachromacy, I didn’t understand the extent of the differences in what I’m seeing and what regular folks are seeing – Concetta Antico

The experiment tested the participants’ sensitivity to different levels of “luminance! at certain wavelengths of light; put simply, with Antico’s eye’s extra cone, she should be picking up more light, meaning that she could see very subtle differences in the brightness of certain shades. Sure enough, Antico proved to be more sensitive than the average person, particularly when looking at reddish tones – a finding that perfectly matched the predictions from her genetic test.

As Jameson had suspected, Antico also performed much better than the other potential tetrachromat who was not an artist – supporting the idea that her colour training had been crucial for the development of her abilities.

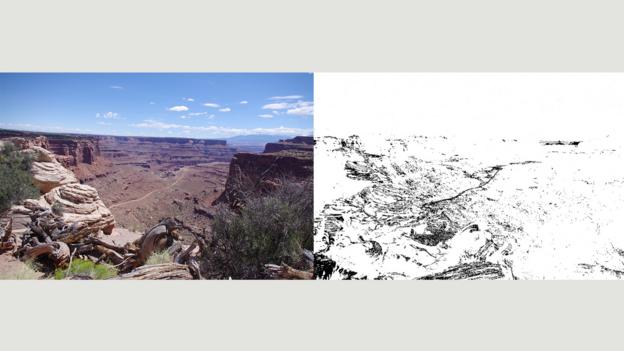

Jameson’s experiments allow her to simulate Antico’s vision. The black dots reveal the areas affected by her extra “cone” – about a third of the image (Credit: Kimberly Jameson)

Using these results, Jameson then reconstructed some photos to give us a better idea of the way the world may look to Antico. Although it would be impossible to recreate the exact picture she sees, the photos highlight which areas would be most sensitive to Antico; in the scene above, for instance, the highlighted patches show the areas most affected by her tetrachromacy. When I ask her what the scene would look like in her eyes, she says the hillsides are orangey pink, while there tends to be a lot of violet in the deadwood. Grass, she says, is iridescent, and the bushes are “bright orange yellow olive green”.

“Now I have a whole new appreciation of what everybody else is not seeing,” she says. “It’s very shocking to me. Even when I found out I had tetrachromacy, I didn’t understand the extent of the differences in what I’m seeing and what regular folks are seeing.”

Jameson has now started to study other tetrachromat artists (including Antico’s sister) – so the hope is that she will be able to study how their ability is reflected in their artistic style. So far, it looks like Antico’s paintings show the same kinds of details that might be predicted by Jameson and Winkler’s simulations.

Antico, for one, hopes to use Jameson’s simulations as a guide in her art classes; by encouraging people to focus on the areas that are most vibrant for her, she hopes they may be able to train their eyes to be more sensitive.

She already thinks she’s seen some results. “Just yesterday, I was out walking with my students, and one of them said ‘look at the violet in that bush – I would have never seen that without you’,” she says.

—

Source: (BBC, David Robson)

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.